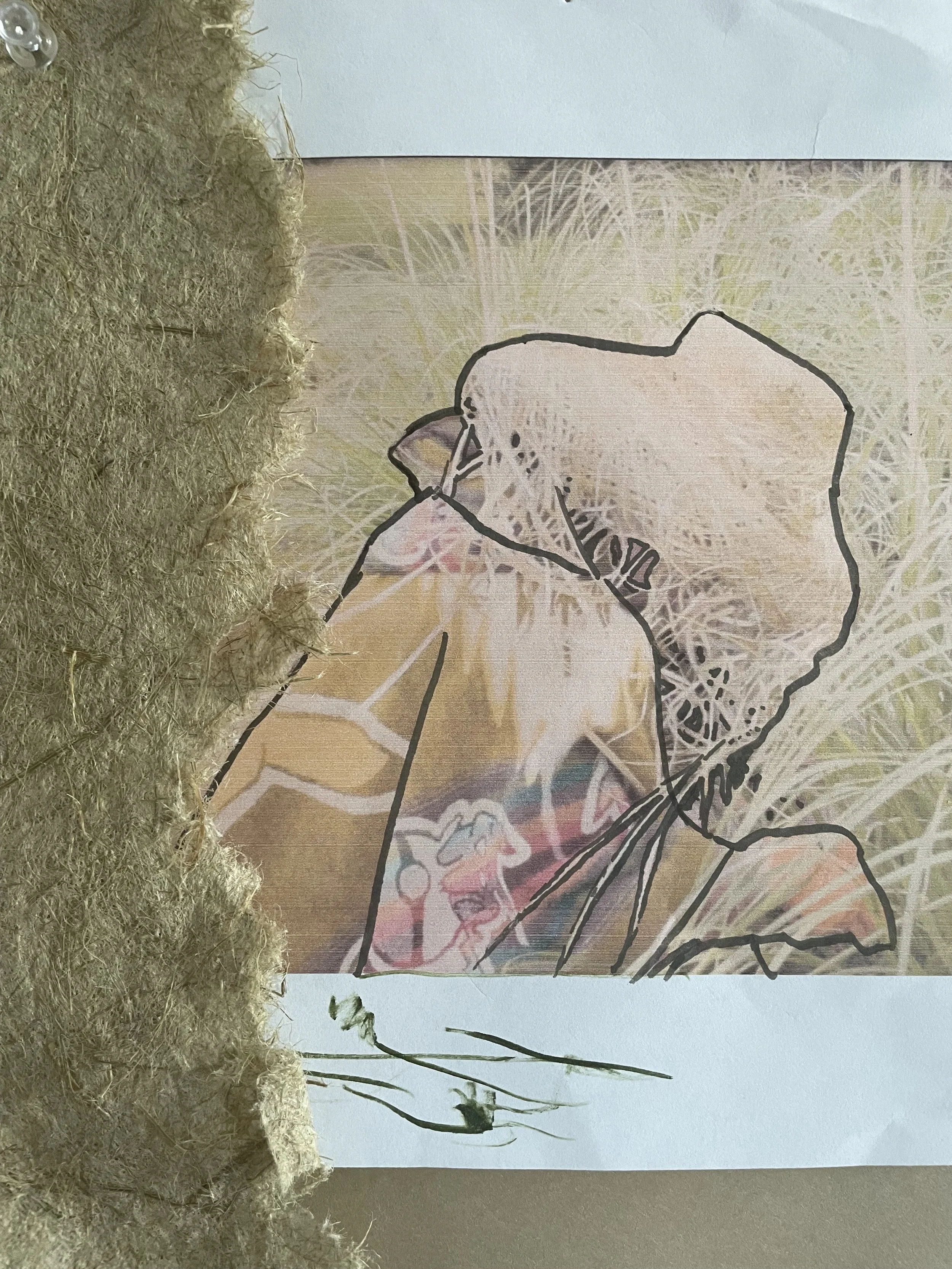

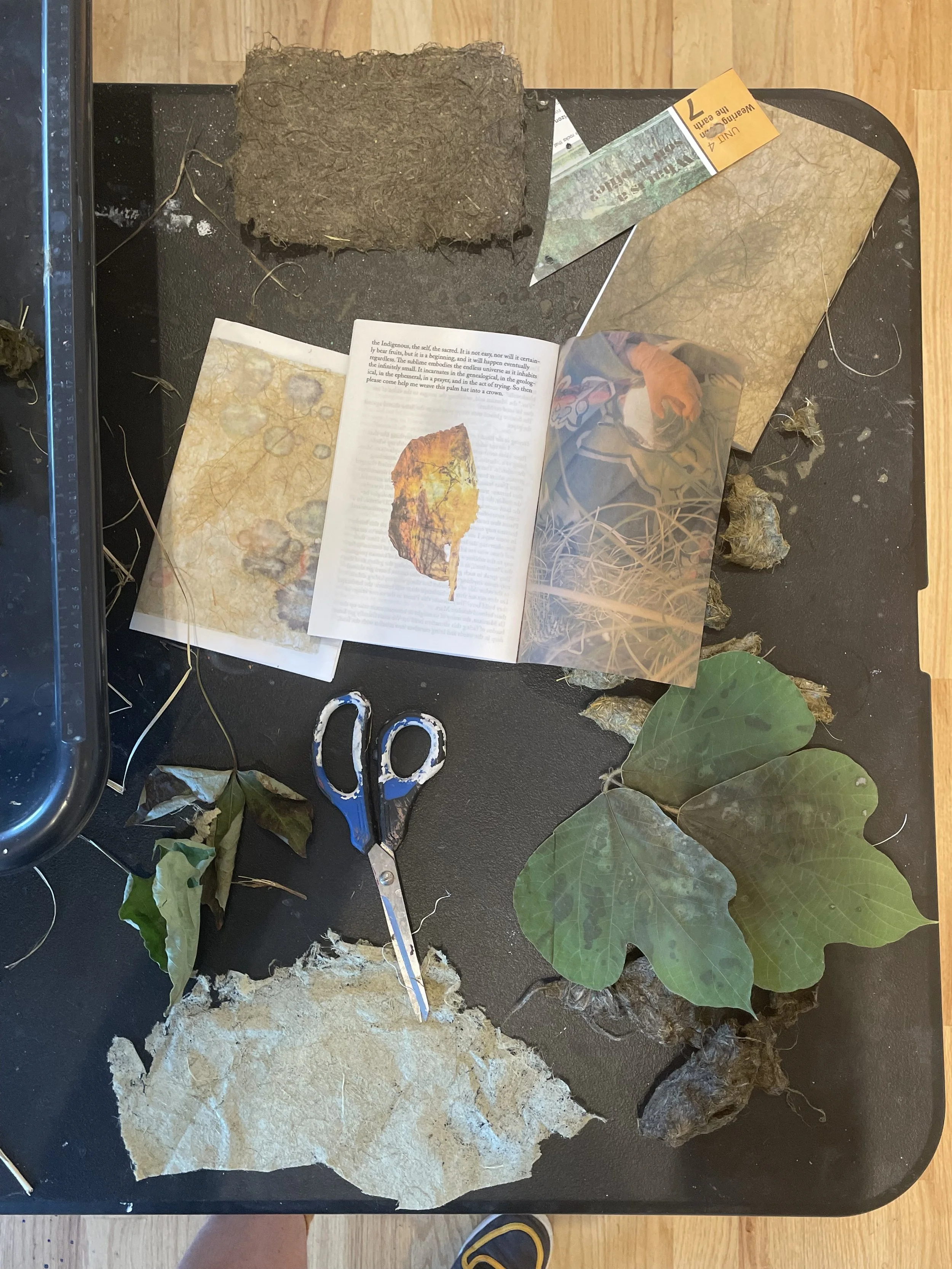

Jules in his studio. Photo taken by Cam Clark.

Aspen Sanderson, Fall Intern, in conversation with Jules Sease. Jules Sease is an interdisciplinary artist whose work explores the multifaceted aspects of the transgender experience, mental health, queer relationships, and the simple joy of dogs. His diverse artistic practice encompasses oil painting, fiber art, metalwork, and charcoal drawing, resulting in a rich tapestry of images, quilts, and sculptures. Currently based in Baltimore, Maryland, Julian shares his home with Sebastian the cat and Ruby the elderly pitbull.

Jules will be leading a quilting workshop on Saturday, November 15. Click HERE to sign up.

///////////////

Aspen: So, would you like to introduce yourself?

Jules: Yeah! My name is Jules Sease, I am originally from Austin Texas, I live in Baltimore currently. I’m 25. Yeah, that’s me.

Aspen: Cool. If you were a vegetable, which one would you be?

Jules: Ooh, good question. I think an artichoke. I got a big heart, I think. And I also really like artichokes, but I’ve only had them twice.

Aspen: You gotta get more vegetables in your system.

Jules: I do.

Aspen: So why/when did you start creating art?

Jules: I’ve always done art, since I was little. I have a really creative aunt who was really supportive of arts always. Same with my mom, and my dad. I just come from a creative family. But in high school, I really started doing sketchbooks a lot to cope with mental health stuff. And since then it’s been all-consuming.

Aspen: What brought you to Stove Works?

Jules: I was applying to a bunch of residencies, I applied to this one thinking it was kinda cool and kinda quirky. And I love the South. So I applied here, and I got in! That’s what brought me here, I got in.

Aspen: What do you like so far about Stove Works?

Jules: I’ve liked the people a lot, I’ve liked the people that I’ve met, the artists that I’ve met, the director team and everyone and the staff. It’s truly the gift of time here, and then the facilities are great.

Aspen: What are you most excited for with your workshop on the 15th?

Jules: I think quilting is amazing. And I am so excited to share it with people. It’s such a community act, and being a part of a thing that creates community is always so fun. I’m so excited to be able to bring people together to teach a skill that they may not know.

Aspen: Yeah. I mean, I’m excited. Speaking of quilting, what made you want to incorporate it into your artistic practice?

Jules: My mother’s side has always quilted. All the blankets in our house are quilts. And they’re always this labor of love. And so I started making them, they taught me how to make them. From there I thought they were really interesting objects of significance, of comfort, and are really heavy with meaning. So they became part of my practice.

Aspen: Did they teach you as a kid or did you ask them to teach you?

Jules: As a kid, and a little bit when I was older, but mainly whenever I was younger. During the pandemic was when I made my first full-size quilt, and from there I’ve just been making quilts.

Aspen: So you’ve been at Stove Works for a month so far, and you’re staying on for this next month. What are you excited to be working on this month?

Jules: I’m really excited about this metal quilt. I’m really excited about doing paintings of the metal quilt. That is something I’ve never done before, paint my sculptural work, and it’s been really fun so far, so I’m really excited about that.

Aspen: Okay, my last question. Would you rather be able to speak with animals or transform into one?

Jules: Ooh, I think. Would I be able to speak with them if I was also the animal?

Aspen: Hmm. I’m gonna say no, since that’s the other option.

Jules: Okay, okay, okay, okay. I think I would rather speak with them.

Aspen: Yeah, that’s fair.

Jules: Ask Gertrude why she hates me so much.

[Gertrude is Stove Works’ gallery pup!]